Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- The Role Of Assistant Principals...

The Role of Assistant Principals

Evidence and Insights for Advancing School Leadership

- Author(s)

- Ellen Goldring, Mollie Rubin, and Mariesa Herrmann

- Publisher(s)

- Vanderbilt University and Mathematica Policy Research

Summary

How we did this

This report is a synthesis of 79 empirical research studies on assistant principals published since 2000, including both quantitative and qualitative studies. It also includes new analyses of national data and data from two states, Tennessee and Pennsylvania. This report provides a descriptive portrait of the assistant principal role. It then addresses two important issues:

diversity and equity among assistant principals;

assistant principals’ influence on student and school outcomes.

Assistant principals are a growing presence in schools. Yet the importance of the role is often overlooked. This report found that the assistant principal role has untapped potential to achieve three important goals:

- Diversifying the principalship

- Preparing effective principals

- Achieving equitable outcomes for students.

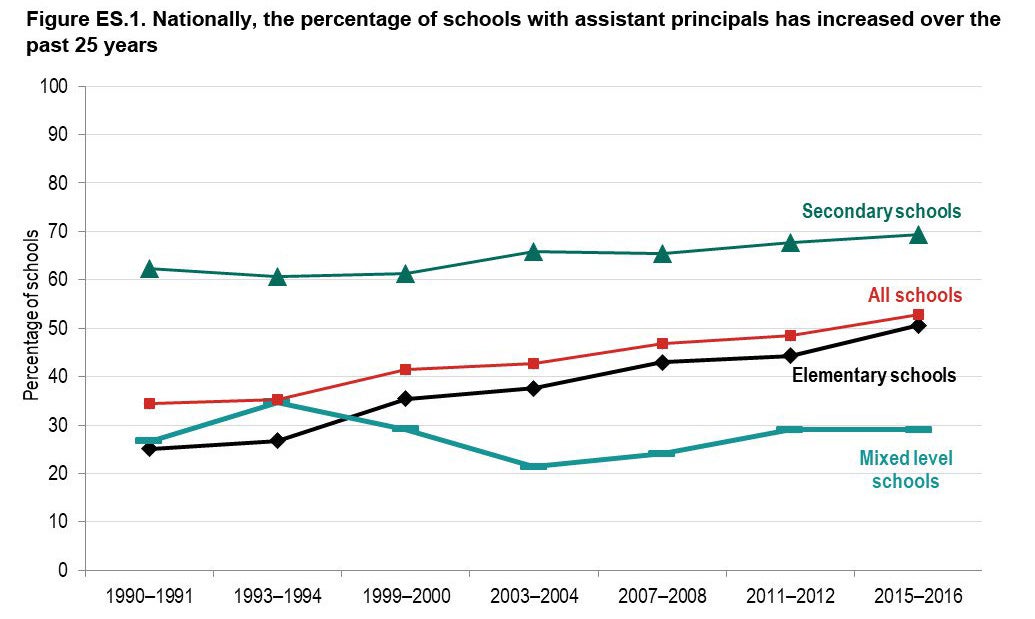

The number of assistant principals has increased dramatically in recent years. That is one reason for the growing importance of the role. Between 1990–91 and 2015–16, the number of assistant principals increased by 83 percent, from about 44,000 to 81,000. Over the same period, the proportion of schools with the position jumped from one-third to one-half.

As a result, today about three-quarters of principals have spent time as an assistant principal. That makes the role “an increasingly common stepping-stone” in a school leadership career.

Diversifying the Principalship

Racial and gender disparities exist in the principalship. The report looked at available national data. Because the data are limited, they also analyzed data from six states: Illinois, Iowa, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee. The report found:

- Nationally, principals of color are more likely to have had experience as an assistant principal than white principals. There is limited evidence to explain why white educators are more likely to advance directly to the principalship. The authors find evidence suggesting two possible reasons: hiring discrimination and less access to mentoring, especially for female APs of color.

- People of color are underrepresented among educators, relative to the student population. In the six states studied, 34% of students were students of color. That’s more than the proportion of people of color who are assistant principals (24%), principals (19%) or teachers (13%.)

- A higher proportion of assistant principals across the six states are people of color (24%) than are principals (19%) and teachers (13%).

- Women are less likely to become assistant principals or principals than men. In the six states studied, 77% of teachers were women. But a smaller proportion (52%) of both principals and assistant principals were women.

- Studies of barriers to women becoming assistant principals and principals had mixed findings. Some suggest that reasons could include family responsibilities, hiring bias, and less mentoring and encouragement to become a leader.

The authors recommended strategies for overcoming racial and gender disparities. These included more structured recruitment and mentoring of people of color and women for school leadership. Strategies also included clearer policies for advancement.

Preparing Effective Principals

Research on how the assistant principalship prepares educators to become principals is scarce. There is little evidence of a relationship between assistant principal experience and future principal performance. Studies indicate that principals with assistant principal experience generally perform no differently than principals without assistant principal experience. But serving as an assistant principal in a more effective school might be related to improved student achievement. Also, many principals believe that prior experience as an assistant principal was instrumental to their work as principals.

The report notes many weaknesses in the professional development of assistant principals. The authors believe that overcoming these weaknesses could better prepare assistant principals to become principals.

Weaknesses in assistant principal preparation include:

- Assistant principals are not given systematic, sequential, or comprehensive leadership-building opportunities. They also lack ongoing evaluative feedback in preparation for the principalship.

- Assistant principals in rural areas and smaller districts have disadvantages. These include less access to mentoring, professional development, and networking activities.

- There are no standards for assistant principals that are consistent with the role’s function as preparation for the principalship.

Achieving Equitable Outcomes for Students

Limited evidence exists about whether and how assistant principals contribute to improved student and school outcomes. One study indicated that an instructional leadership role for assistant principals improves student achievement. Other research suggested that assistant principals could address bias and inequality through their attention to cultural inclusivity and equitable learning environments. Assistant principals’ work with students, teachers, and families means they can play important roles in improving students’ academic, social-emotional, and behavioral outcomes.

Key Takeways

- The number of assistant principals has increased dramatically in recent years. Between 1990–91 and 2015–16, the number of assistant principals increased by 83 percent: from about 44,000 to 81,000. Over the same period, the proportion of schools with the position jumped from one-third to one-half.

- The assistant principal role has become “an increasingly common-stepping stone” to becoming a school principal. About three-quarters of principals have spent time as an assistant principal.

- The report notes many weaknesses in the professional development of assistant principals. These include a lack of systematic, sequential, or comprehensive leadership-building opportunities or ongoing evaluative feedback in preparation for the principalship.

- People of color and women are not equitably promoted to the principalship. More structured recruitment and mentoring of people of color and women for school leadership and clearer policies for advancement could help overcome this.

- With better training and development, assistant principals could make more powerful contributions to improving schools and advancing educational equity for students. They could also be better prepared for the principalship.

Visualizations

Materials & Downloads

What We Don't Know

The synthesis suggests important gaps in the knowledge base, raising the following questions for future research:

- Which assistant principal roles are most related to improved student and school outcomes?

- How can assistant principals best advance equity for students and teachers?

- What are the most effective approaches to preparing and developing assistant principals?

- Which experiences as an assistant principal are most related to future principal performance, including in advancing equity for students and teachers?

- Why are educators of color more likely to become assistant principals than white educators and less likely to advance directly to the principalship?

- How can experiences in the pathway from teacher to principal become more equitable for educators of color and female educators?