They are items on every school district’s to-do list: Reduce chronic absenteeism. Improve teacher satisfaction and retention. Bolster student learning. Now a major new research review points to the person who can have a positive impact on all of these priorities—the school principal. The groundbreaking study, How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research, finds that replacing a below-average principal at the 25th percentile of effectiveness with an above-average principal at the 75th percentile increases the average student’s learning by nearly three months in math and reading annually. Schools led by strong principals also have higher student attendance and greater teacher retention and satisfaction, according to the report.

Recently, the Wallace Blog caught up with the report’s authors, Jason A. Grissom, the Patricia and Rodes Hart professor at Vanderbilt University; Anna J. Egalite, associate professor at North Carolina State University; and Constance A. Lindsay, assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, to discuss their findings and implications for the field. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

After the release of the report, some people were asking on social media if a great principal is more important than a great teacher and you had a great response. Can you share it with us?

Grissom: You can’t directly compare the effects of teachers and principals because the effects of a principal are largely through their work to expose kids to great teachers. It’s helpful to think about it from different points of view. From the student’s point of view, the teacher is clearly the most important person because he or she has the most direct effect on what I learn and my other outcomes. For the life of a school, the principal is certainly among the most important people, maybe the most important person, in part because principals are the ones who hire great teachers, ensure that great teachers stay in the building, and set the conditions for teachers to be able to teach to their full potential.

The report tries to emphasize how large the impacts of principals are and also what the scope of those effects are. Even if you just focus on student test scores, the report uses this size-plus-scope-of-effect to argue that we really should be investing in principal leadership. We’d go so far as to say that if you could only invest in one adult in the school building, then that person should pretty clearly be the principal.

Given the research evidence showing the positive effects that a principal can have on student learning and other important outcomes, how can the field help less-effective principals improve?

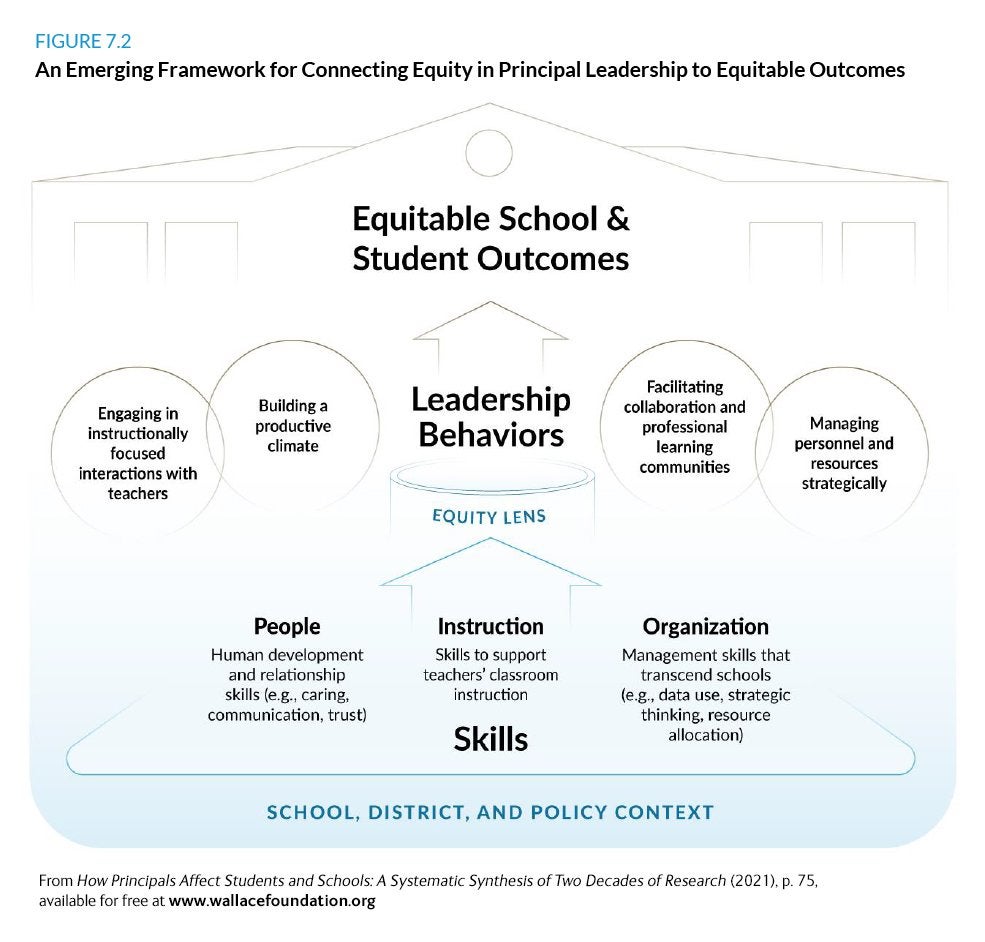

Egalite: That’s the question we tried to answer in the second part of the report, which identifies the four leadership behaviors of great principals: engaging in instructionally-focused interactions with teachers, building a productive school climate, facilitating collaboration and professional learning communities, and managing personnel and resources strategically. If you were designing professional development for below-average principals, these are the four areas you could lean on that the evidence shows are associated with better outcomes in the long run.

Which instructionally-focused activities appear particularly effective—and which ones not so much?

Egalite: One effective activity is the use of data. Principals can encourage teacher buy-in by using data to monitor student progress and demonstrate changes in student achievement. Another is teacher evaluations, which have become more sophisticated in recent years. They no longer just analyze student test scores to say if someone is a good teacher or a bad teacher, but marry that information with other data points collected through classroom observations and other measures.

Grissom: We tried to highlight engagement with instruction as separate from a more general, and maybe ill-defined notion, of what it means to be an instructional leader. Some principals have internalized the message that instructional leadership means being in classrooms. But simply being present is not associated with greater student growth. It may even have negative effects because having the principal in the classroom is distracting for both the students and the teacher. Maybe that distraction is worth it if the principal follows up with support for the teacher’s work and uses data from the observations to help drive the instructional program. But on its own, it’s not enough to move the needle.

The report found that principals can have an important impact on marginalized populations, including students from low-income households and students of color. How does an equity-focused principal exhibit the four leadership behaviors?

Lindsay: They infuse all the activities they usually do with an equity focus. With regard to instruction, it would mean working with teachers to adopt a more culturally responsive pedagogy. It means making sure that teachers are engaging in practices that are relevant to all students in the school. In building a productive school climate, it means working with families and thinking about the community context.

Grissom: Thinking about how equity can be infused into these domains of behavior is clearly an area we need to know more about. The report offers lots of examples from the research base that exists, but the evidence is still developing.

You also found widening racial and ethnic gaps between principals and the students they serve. What are some tactics that districts can use to diversify the principal workforce?

Lindsay: The key is diversifying the teacher workforce, because principals start as teachers. In terms of district actions, there are strategies like “grow your own” programs where districts identify and develop individuals in-house who are well-suited to meeting the needs of their community. Districts can also examine different stages of the educator human capital pipeline to identify places where people of color drop out and then work to shore up those stages.

Grissom: We’ve had concerns for a long time that access to the principalship in a lot of areas is driven by who you know within a district. That likely disadvantages people who are not in power. In response, districts are increasingly formalizing leadership programs with predefined selection criteria, ensuring that people are getting into the principal pipeline on the basis of their capacity for leadership. And at the end of the pipeline, there has to be an equitable hiring and selection process. Diversifying the pipeline is an area we have to learn more about—where is it happening successfully and how, so that those practices can be taken to other places to ensure greater principal diversity.

Based on your report’s findings, what aspect of school leadership would you study right now if money and time were no object?

Lindsay: A lot of the research on equity that we drew from is very localized and context specific. I would study equity in a more systematic way. Just as we have rubrics for other things, I think it would be nice to have one about culturally responsive pedagogy that’s been tested and validated at a wide scale.

Egalite: I’d like to know more, from a measurement perspective, about defining effective principals. I went through a Catholic teacher training program and for a brief moment considered its leadership training program. Their approach to leadership training is very much centered on building the school culture. Test scores are a much later part of the conversation. Private Catholic schools are obviously a different context than public schools, but how a principal sets the tone in a school and gets everyone rowing in the same direction is still relevant. How do you measure that? We rely on test scores to gauge principal effectiveness because they are easily collected by states, but it’s really just one piece of the pie. A more multidimensional view of principal effectiveness would be helpful.

Grissom: I’m interested in how to measure capacity for the skills and behaviors we discuss in the report, so that we can do a better job identifying future leaders, developing their capacities and ensuring they are ready to lead when they enter the principalship. Historically, we have not done a great job of assessing people’s future potential. Maybe this is because we didn’t have the opportunities to develop the tools that measure those capacities. The same tools could also be used once a person is in leadership to identify areas for growth and target professional learning. They could also help us identify excellent leaders so we can draw on their excellence to help other people behind them in the principal pipeline. There are a lot of opportunities to think about how we identify, measure and assess both potential and strength at all phases of the pipeline.

Your report is the first of three research syntheses to be released by Wallace this year. A second will examine the role of the assistant principal and a third will look at the characteristics and outcomes of effective principal preparation programs and on-the-job development. How does it feel to be first out of the gate?

Grissom: We’ve done a few presentations about our report and people have asked how our findings apply to assistant principals and the implications for pre-service preparation and in-service professional learning.

It will be very interesting to see the conversations following the release of the other two reports and how they build on the conversation we’ve been having with the release of ours. Stay tuned.