They are second in command in a school, and yet assistant principals often are not given opportunities to strengthen leadership skills that are vital to their effectiveness in the role as well as in the principal post many will assume one day. That is one of the main takeaways of The Role of Assistant Principals: Evidence and Insights for Advancing School Leadership, a major new research review that synthesizes the findings of 79 studies about APs published since 2000 and includes fresh analyses of national and state data. The review found that the number of APs has grown markedly in the last 25 years and that the role has become a more common stop on the path to the principalship. At the same time, the researchers found disparities in the composition of the leadership workforce. Educators of color are less likely to become principals and more likely to become APs than white educators. Women are less likely than men to become either APs or principals.

Recently, the Wallace Blog spoke with the report’s authors, Ellen Goldring and Mollie Rubin of Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of Education and Human Development, and Mariesa Herrmann of Mathematica, about their findings and the implications for district policies and practices. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The number of APs has grown six times faster than the number of principals in the last 25 years. Why do you think that is?

Herrmann: We looked into whether it was due to an increased number of students in elementary schools and found that explained some but not all of the increase. You’re still seeing an increase in the assistant principal-student ratio in elementary schools over this time period.

Goldring: That’s important, because at least officially, districts might have a funding formula that says if a school is of a particular size, it gets an AP position. But we also surmise that local districts can certainly fund positions differently. They might combine a coaching position with a teacher-leader position and turn that into an AP position. We have no idea why [the increase] is happening, the implications vis-à-vis other staffing decisions and what the rationale might be for a district or principal to think that the AP position is a better role to help fulfill the needs of a school as compared to other positions.

The synthesis found uneven opportunities for advancement for educators of color and women in the leadership pipeline. Does the research suggest reasons why? What measures could be taken to promote equitable opportunities?

Herrmann: For educators of color, the research mentions things like differences in access to mentoring, particularly for Black women. It also suggests hiring discrimination, such as people of color not being considered for suburban schools or schools with predominately white student populations. One African American female educator in a study had a nice quote about this; she was not hired and informed that she wasn’t the right “fit.” She said, “Most of the [African American female administrators in our district]…are placed in high-poverty schools. Perhaps this is where we fit?” There’s also some evidence of differences in assigned leadership tasks by race, which could prevent people’s advancement. For women, there are a bunch of explanations—differences in access to mentorship, differences in assigned tasks, family responsibilities and the time commitments of being an assistant principal or a principal, differences in aspirations or confidence, and also discrimination.

Goldring: The point about not being a “good fit” is something to emphasize. There’s probably a lot of both explicit and implicit bias about where leaders of color want to be placed, should be placed and the implications for their career trajectories. We suggest using equity audits and leader tracking systems [which compile data on the backgrounds and careers of potential and sitting school leaders] to bring patterns to light and show how they play out in different types of schools. It’s an important first step but beyond that, districts need to create spaces for people to have really honest and open conversations about the patterns. That is key to addressing them.

Hermann: Besides just understanding the patterns, I think addressing this requires mentoring people of color and women. Someone who is already a principal can help them understand how to be a leader in that particular district. Maybe to the extent that they share similar backgrounds or experiences, they can relate to that person.

Rubin: It’s also about making space to hear the experiences of people who are facing differential outcomes and how they’re experiencing the roles that they’re in. We often assume that we know what we’re trying to fix, but we don’t necessarily understand it at a deep level.

Principals today are more likely to have served as assistant principals than in the past. Many say that the experience was pivotal to their leadership preparation. What makes a strong principal-assistant principal mentoring relationship?

Herrmann: One study mentioned areas where assistant principals found advice and mentoring useful. One was skills development, such as building strong relationships, honing decision-making skills, having strong communications skills. This suggests that principals need to have strong leadership skills themselves, so that they can model them for the assistant principal.

Goldring: We noted in our report that there are no studies on how principals think about or conceptualize the role of assistant principals. We don’t know why an assistant principal might spend more time on task A or task B, or what principals consider when they hire assistant principals. There are gaps in terms of the research as well.

Your question brings out the important notion of the relationship between the assistant principal role and their evaluation, and the extent to which there is systematic, competency-based formative feedback that’s built into both the role of and the relationship between the assistant principal and the principal. In most cases, principals and assistant principals are evaluated on the same rubric. The few studies that talk about the assistant principal experience with evaluation note a lot of ambiguity. In one study, the assistant principals did not even know if they were formally evaluated or how. Another study mentioned the complexity of using the same rubric: If I’m an assistant principal and evaluated on the same rubric as the principal, does that mean I can never be exemplary because that’s only for principals? What does this mean for the types of tasks and leadership opportunities that an assistant principal has?

Rubin: A principal might assign tasks to their assistant principal to fill in for their own weaknesses. Together they make one really powerful team, but when it comes to the assistant principal’s evaluation, what does it say? They may not have the opportunities to do or learn certain things.

The pandemic has upended education and created unprecedented challenges for school leaders this year. Has it heightened awareness of the role of assistant principals? Could it lead to lasting change to the job and if so, how?

Goldring: During National Assistant Principals Week, I facilitated a webinar with a panel of four assistant principals about their role during COVID. The most important point they wanted to bring home was that they are school leaders in their own right and that this year highlighted their overall importance as part of the leadership team. They are not assistants to their principals. It was a nice link to the importance of assistant principals having opportunities to really be school leaders and not necessarily be the assistant principal of X—of student affairs, of curriculum and instruction, of a particular grade level. COVID put the focus on the complexity of school leadership and the need for partners in that work. You really need more than one leader.

Rubin: I worry that in some ways, assistant principals may once again slip through the cracks. I keep hearing that assistant principals have become COVID contact tracers. That says a lot about how nebulous the job is. “Who’s going to do contact tracing? Oh, the AP can!” Principals who have lost their assistant principals, perhaps in the last recession, will be the first to tell you how important they are. But at the same time, there seems to be a lack of recognition and attention paid to the role. Perhaps it needs to be more deliberate.

Your report found that assistant principals have been seriously under-studied. If money and time were no object, what would you study about the role?

Rubin: I would love to watch the changes that happen when districts decide to invest in the assistant principal position—how they define the role to align with their vision and goals, and how it plays out in schools in terms of interpersonal dynamics, such as the relationships between assistant principals and principals, assistant principals and teacher leaders.

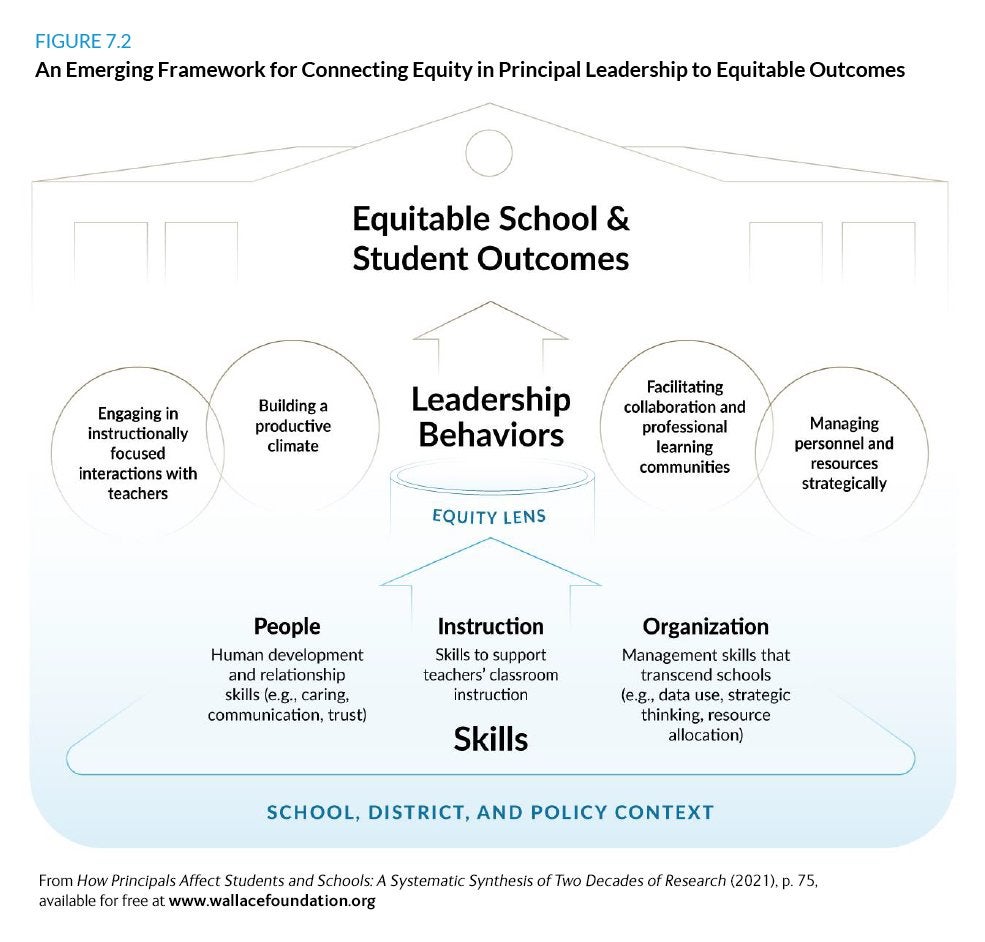

There’s also a study I want Mariesa to do because I don’t do this kind of work. We don’t know a whole lot about the effects of assistant principals or the effects of serving as an assistant principal on leader performance. I hypothesize that’s because the role is so nebulous. My question is, what are the leadership tasks that lead to the outcomes we’d like to see, both in terms of evaluation performance as an assistant principal and later as a principal, as well as outcomes for students, school and staff. If you could really figure out what matters most, then you could create a model of an assistant principalship that’s constant at a district level.

Herrmann: Mollie did a really good job there! Assistant principal roles vary considerably and I think we need to better understand what aspects are most important for improving student learning and well-being. Are there ways the role can be better leveraged to improve outcomes for students? I don’t know if the role actually has to be constant across a district. I think you could investigate how it should be different, based on the local context, and what to take into account when developing the role.

Rubin: I wish I could fund you, Mariesa.

Goldring: One of our big problems is that we have very blunt measuring instruments. We say that assistant principals’ tasks vary, but the way in which that has been measured is very unsatisfactory and leading to misunderstanding and misreporting. Researchers typically ask assistant principals how they spend their time, but no two studies ask that question similarly. In some studies, time is reported for a typical week, sometimes it’s not even clear what the timeframe is. We also need to rethink categories of tasks. Why is student disciplinary work not considered instructionally focused? If you’re working with a student to be more focused in class, isn’t that core instruction work? This is deep conceptual work that could greatly enhance the field.

The second thing that has emerged for me is trying to understand how and why some assistant principals choose to make the role a stepping-stone to the principalship while others choose to stay in the role and make it their own leadership position in its own right, alongside the principal. Is it an individual preference, a district preference, something in the school context and the way that leaders are developing teams? If we understood this, we would be better able to counsel and speak about the options to teachers who are coming up through the ranks.