Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- A New Role Emerges For Principal...

A New Role Emerges For Principal Supervisors

Evidence from Six Districts in the Principal Supervisor Initiative

- Author(s)

- Ellen B. Goldring, Jason A. Grissom, Mollie Rubin, Laura K. Rogers, Michael Neel, and Melissa Clark

- Publisher(s)

- Vanderbilt University and Mathematica Policy Research

Summary

How we did this

Methods for the research behind this report included interviews and surveys. The study was conducted by independent research teams at Vanderbilt University and Mathematica. Their work focused on the experiences of the six school districts that took part in the Principal Supervisor Initiative. It looked at how the districts implemented the effort during its first three years, from the 2014-2015 to 2016-2017 school years.

In many large school districts, principal supervisors face sprawling jobs. They may oversee two dozen schools. Their duties include tasks in administration, operations, and compliance. That often leaves them little time to provide principals with the support they need to improve teaching and learning.

In 2014, six large school districts began a four-year effort to redesign the principal supervisor role to focus on improving instructional leadership.

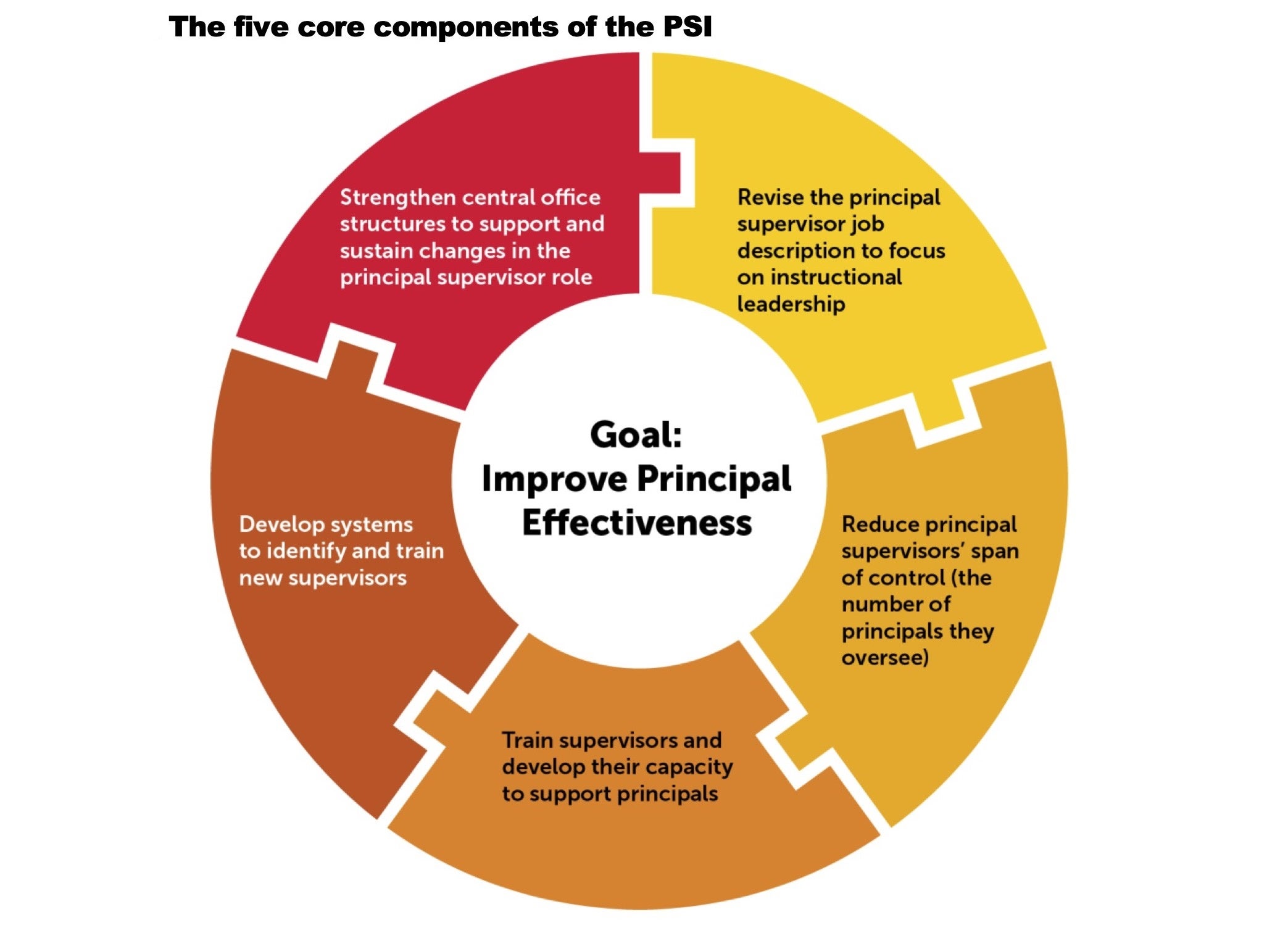

This study examines the first three years of the Wallace-funded Principal Supervisor Initiative. It finds that districts were able to transform the principal supervisor role in these ways:

- Revising the principal supervisors’ job description. Districts created a new definition of the supervisor role. To do so, most drew on the 2015 Model Principal Supervisor Professional Standards by the Council of Chief State School Officers. The districts also sought input from principal supervisors, principals, central office staffers, and outside experts.

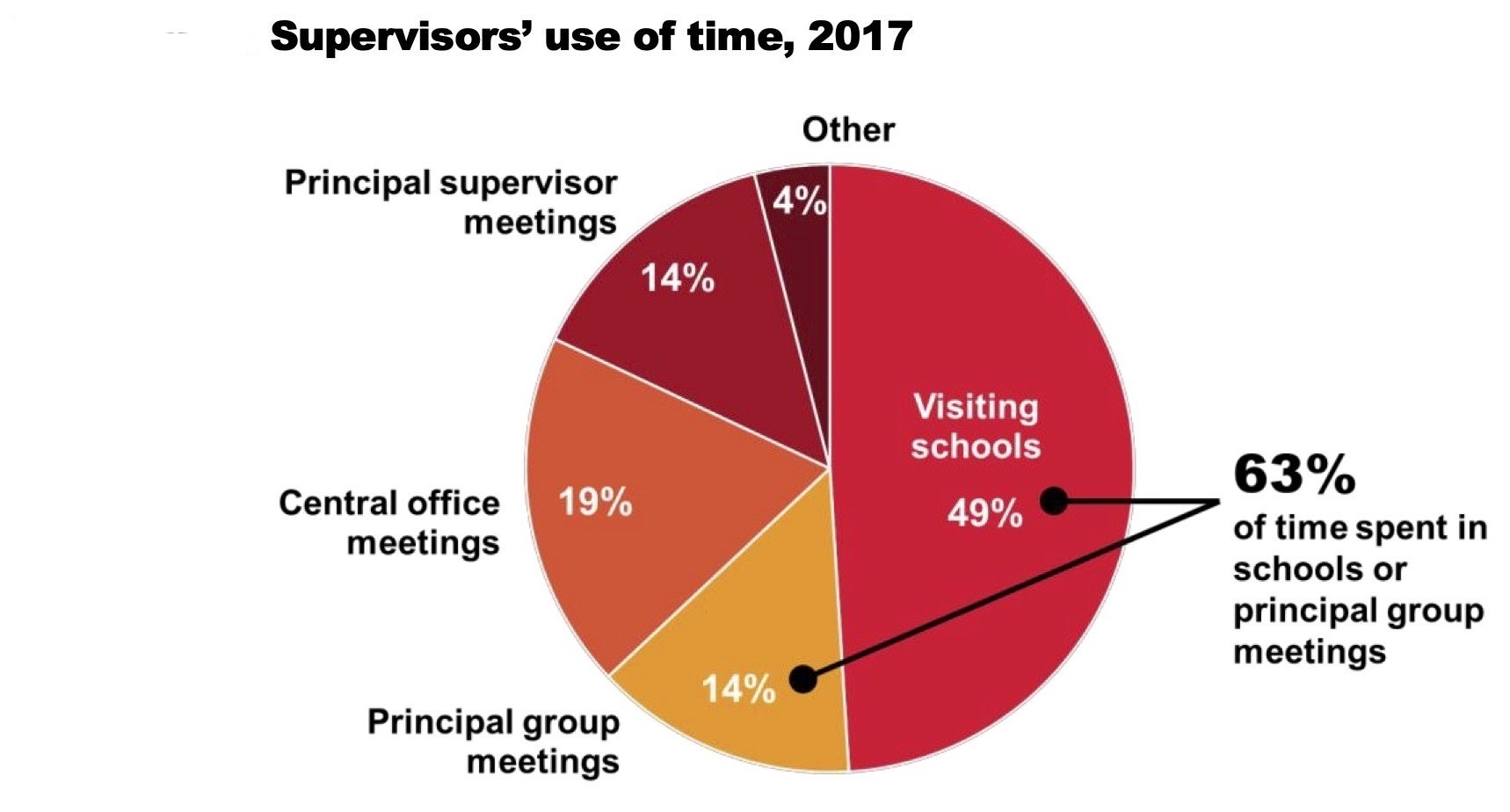

- Reducing the number of principals assigned to each supervisor. Districts succeeded in lowering the average number of principals-per-supervisor to 12 from 17. That meant that supervisors were able to spend more time with their assigned principals. By the third year, supervisors reported spending 63 percent of their time with principals.

- Training principal supervisors to better support instructional leadership. Supervisor training focused heavily on understanding and identifying high-quality instruction. It also focused on developing principals as instructional leaders. Supervisors especially valued one-on-one coaching from trainers and observation of their peers’ work in schools.

- Developing systems to identify and train new supervisors. Three districts created apprenticeship programs for aspiring supervisors. These programs offered a mix of mentorship and formal training. Apprentices got hands-on experiences, such as planning professional development for principal networks.

- Reorganizing the central office to better support the new principal supervisor role. Districts assigned central office staff members to a number of responsibilities formerly held by principal supervisors. That left supervisors with more time to focus on instruction. Districts created new structures to support collaboration and coordination across departments. They also improved systems of communication among the central office, supervisors, and schools.

For the first time, most supervisors received systematic, job-specific professional development aligned with the new role.

The effort was not without challenges

For example, the skill level of principal supervisors varied greatly. Many supervisors felt overburdened. A number of central office administrators resisted changes needed to better support schools. The report recommends steps to address these challenges in the initiative’s final year and beyond. These include steps to improve supervisor training, modify job expectations, and improve central office culture.

Participating districts were:

- Broward County, Fla.

- Baltimore

- Cleveland

- Des Moines

- Long Beach, Calif.

- Minneapolis

Key Takeaways

- Principal supervisors have traditionally focused on administration, operations, and compliance. Six large districts successfully redesigned the job to focus on instructional leadership. The first step was to create a new job description based on professional standards and input from stakeholders and experts.

- Districts succeeded in lowering the average number of principals-per-supervisor to 12 from 17. That meant that principals were able to spend more time interacting with their supervisors.

- Supervisor training focused heavily on understanding and identifying high-quality instruction. It also focused on developing principals as instructional leaders. Three districts developed apprenticeship programs for aspiring supervisors.

- Districts reorganized their central office to better support the new principal supervisor role. Districts assigned central office staff members some responsibilities formerly held by principal supervisors. That left supervisors with more time to focus on instruction. Districts created new structures to support collaboration and communications.

- The effort faced many challenges. Principal supervisor skills varied greatly. Many in the central office resisted changes needed to better support schools. Many supervisors felt overburdened.

Visualizations

Five Core Components of the Principal Supervisor Initiative

Principal Supervisors' Use of Time, 2017